Hurricane Basics

Hurricanes are large weather systems which can produce very strong winds, heavy rainfall, storm surge, and even tornadoes. One sign of the strength of a hurricane is the relatively low air pressure at the center of the storm. This low pressure system results in counter-clockwise flow around the center of the hurricane in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise flow in the Southern Hemisphere.

Around the world, hurricanes may have many different names. The general term for a hurricane is “tropical cyclone.” Tropical cyclones are typically classified by how strong the strongest sustained winds are near the center of the cyclone. For example, the Saffir-Simpson scale, used to classify tropical cyclones near the United States, rates hurricanes from Category 1 to Category 5, with Category 1 storms having at least 74 mile per hour winds and Category 5 having at least 157 mile per hour winds. However, strong winds are not the only potential threat from tropical cyclones. Hurricanes can result in heavy rainfall, especially if they are moving very slowly, and they typically cause storm surge, which is the rising sea levels along the coast caused by the strong winds from a hurricane.

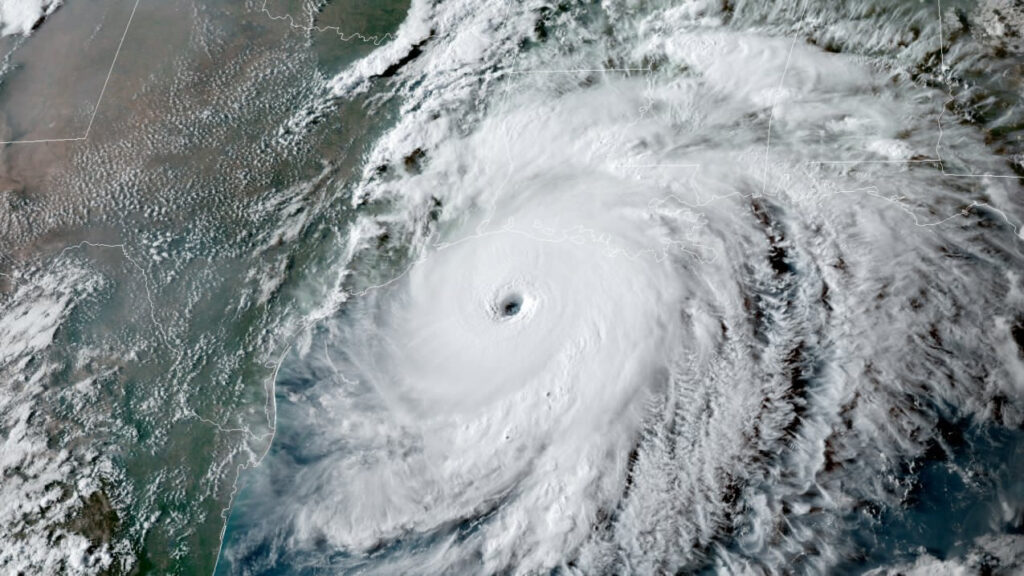

Mature hurricanes generally have three main parts, each with very different conditions and hazards. At the very center of a tropical cyclone is the “eye,” which is a small region of mostly calm winds and clear or partly cloudy skies. The eye is typically located where the lowest air pressure values are. Surrounding the eye is a circular region of very intense thunderstorms called the “eyewall.” The eyewall is typically where the strongest sustained winds are located within a hurricane, but the strongest winds may only be in one section of the eyewall. Stemming out from the eyewall are the outer rainbands of a hurricane. These outer rainbands can still bring gusty winds and heavy rainfall, but they are typically not as strong as the convection within the eyewall. These outer rainbands may contain brief, weak tornadoes which can cause locally strong wind damage far from the eyewall.

The eye of a hurricane can vary in size, but it is typically between 20 and 40 miles in diameter. Likewise, the eyewall, which surrounds the eye, can change in diameter as well, depending on the characteristics of the tropical cyclone. The outer rainbands of a tropical cyclone can extend anywhere from 100 to 500 miles away from the eye of the tropical cyclone, but the average tropical cyclone has rainbands which extend about 300 miles away from the center.