Convective Mode

Convective mode refers to how thunderstorms are organized when they form. Generally, severe thunderstorms often form as discrete supercells or linear systems. Both types can lead to damaging winds, large hail, and tornadoes, but supercells with individual updrafts are more likely to produce hail and tornadoes than linear systems. Certain characteristics of the environment determine whether storms will form with individual updrafts, such as in supercells, or with one long, continuous updraft, such as in linear systems.

Discrete Convection

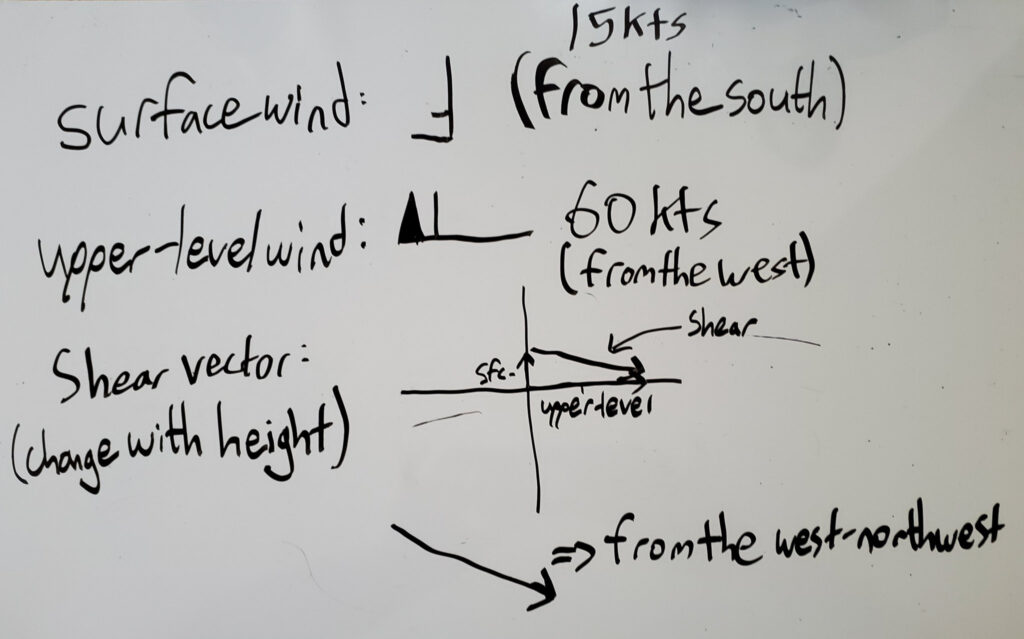

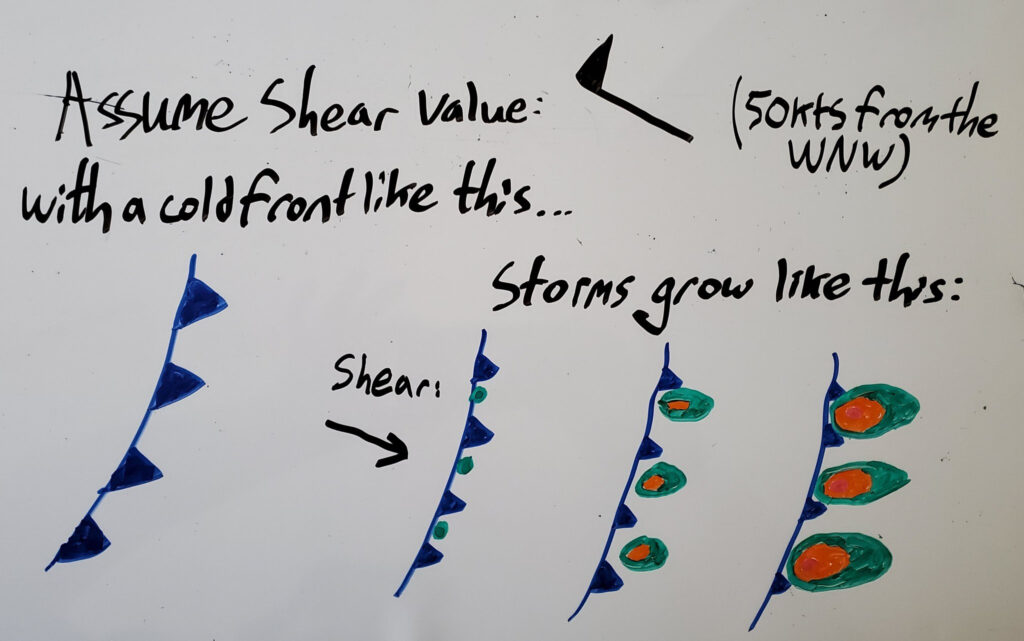

Individual discrete thunderstorms are more likely to form when the vertical wind shear is perpendicular to the boundary acting as the source of lift for thunderstorms. In other words, discrete convection is most likely to occur when wind shear vectors are crossing the surface boundary as opposed to being parallel to that boundary. Environments where the wind shear is perpendicular to the lifting boundary are more favorable for the formation of supercells and tornadoes. However, that does not mean that tornadoes can not form when wind shear is parallel to the lifting boundary.

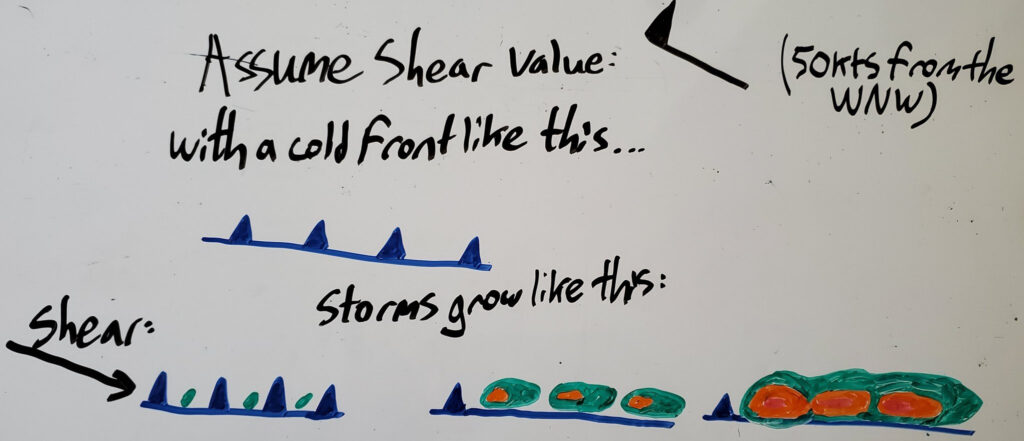

Linear Convection

A line of strong thunderstorms, sometimes referred to as a QLCS (or Quasi-Linear Convective System), usually forms in an environment in which the wind shear is parallel to the initial lifting boundary. In this case, when initial updrafts form along the boundary, the wind shear pushes storms into each other down the boundary, creating the linear convective system. This is in contrast to discrete convection, where the perpendicular wind shear allows updrafts to remain isolated as they grow across the boundary. QLCSs can still lead to dangerous tornadoes, especially since they are more difficult to predict and usually come and go very quickly. Sometimes a violent QLCS tornado can occur between radar scans, which typically happen every five minutes.

In reality, the wind shear is usually not perfectly perpendicular or parallel to the lifting boundary, especially as the orientation of both changes over time. It is common for storms to begin with discrete updrafts in the afternoon to early evening hours and then grow into a linear convective system overnight. This brings a threat of tornadoes and large hail in the afternoon and evening, which shifts to more of a damaging wind threat in the overnight hours.