What are Weather Fronts?

Weather fronts are boundaries between types of air masses. Air masses are typically defined by whether they are dry or moist, and whether they are warm or cold. A cold front is colder air advancing into warmer air, while a warm front is warmer air advancing into colder air. Fronts are also characterized by a stark change in wind direction or speed. Tracking weather fronts is important because most active weather occurs near or close to strong weather fronts.

Cold Fronts

As mentioned earlier, cold fronts are defined when colder air is moving into a warmer air mass. Because colder air is more dense than warmer air, the advancing cold air tends to undercut the warm air. This leads to warm air aloft, which can often help develop severe weather. If you’ve ever felt a really strong cold breeze suddenly come out of nowhere, that was likely a cold front.

Cold fronts are usually shown on weather maps as a blue line with blue triangles pointing in the direction the front is moving.

Warm Fronts

Warm fronts are when warm air is advancing into colder air. Because the warm air is less dense than the colder air, the warmer air tends to want to rise up over the colder air mass. This can also lead to severe weather, as you still have warm air aloft. Oftentimes in weather patterns, you have an area between a warm front and a cold front that is called the warm sector. During severe weather events, the warm sector is usually a place where strong to severe storms are favorable.

Warm fronts are usually shown on weather maps as a red line with red semicircles pointing in the direction the front is moving.

Stationary Fronts

Stationary fronts can have cold or warm air on either side, but the boundary is not moving. Because it is non-moving, you cannot classify it as a warm or a cold front. However, stationary fronts are still important because those boundaries can help initiate or direct strong thunderstorms.

Stationary fronts are usually shown on weather maps as an alternating blue and red line with alternating blue triangles and red semicircles pointing in both directions.

Occluded Fronts

Occluded fronts are a special type of front where a cold front catches up to a warm front. Cold fronts typically move faster than warm fronts because warm fronts are working against the density of the air whereas cold fronts are working with the density of the air. When an occluded front occurs, the chances for severe weather are limited, but impactful heavy rain and snow events can still occur.

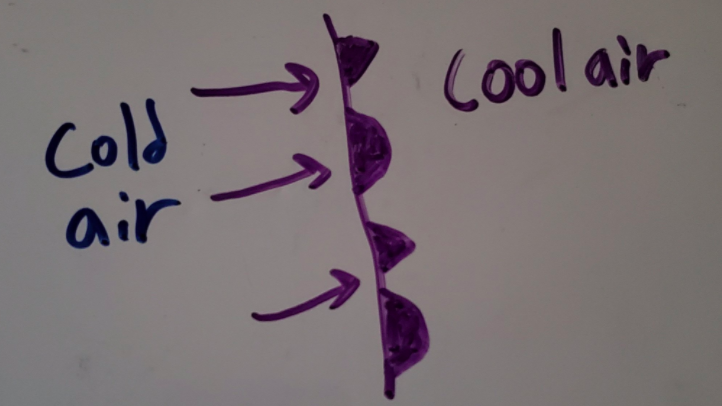

Occluded fronts are usually shown on weather maps as a purple line with purple triangles and semicircles pointing in the direction the front is moving.

Dry Lines

Dry lines are characterized by really dry air moving into relatively moist air. There usually isn’t a strong temperature difference, but there is a really strong relative humidity difference. Because water vapor is less dense than air, the dryer air is more dense than the moist air. This may seem counterintuitive, but dry air weighs more than moist air. This means that advancing dry air along the dry line wants to push the relatively moist air ahead of it up and over the dry line. This can also be a potential source for severe weather as lifting that moist air can initiate strong to severe thunderstorms. Dry lines tend to follow behind cold fronts, but this is not always the case.

Dry lines are usually shown on weather maps as an orange line with orange semicircles pointing in the direction the front is moving.

Other Boundaries

You may have heard of terms like “gust front” or “outflow boundary”. These are boundaries between different types of air masses, just like the fronts we’ve talked about already. However, those terms like “gust front” typically refer to a boundary which is much smaller than typical cold and warm fronts and also does not last as long.